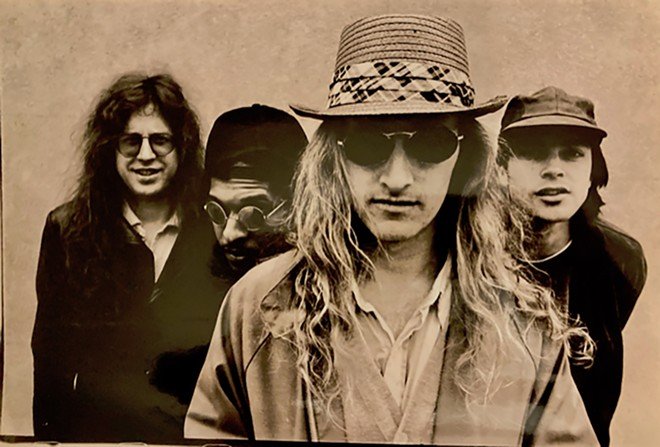

For those of us who grew up steeped in the Columbus music scene, the legend of the Royal Crescent Mob loomed large. Signed by Seymour Stein himself to the legendary Sire records after well-received records on hip NYC label Moving Target and a series of scorching live shows people still talk about with awe.

I started going to shows a bit later, so I grew up seeing the Mob's powerful rhythm section, Harold "Happy" Chichester and Carlton Smith, in a series of tight bands and situations; and every few years there was talk of an RC Mob reunion that no one close to the situation gave any credence to.

With this summer's sad news of Smith being diagnosed with glioblastoma, along with guitarist Brian (B.) Emch losing his wife to cancer this year, and frontman (who left singing for a life tour-managing powerhouse bands) David Ellison's recent treatment for prostate cancer, the band is reuniting for two shows: one here in Columbus on December 16th at the Athenaeum Theatre (tickets here) and one in Covington, Kentucky, the next night at the Madison Theater (tickets here).

I got together with Smith at the Grandview home that's been in his family for over 100 years on a beautiful autumn day to talk about a career in music that's spanned nearly four decades. The below is edited for length and clarity. Thanks to Curt Scheiber for providing background and additional material.

The RC Mob

First off, how are you feeling?

Today is a good day. Most of the days have really been good. Out of the three months since [the diagnosis]. I mean, the symptom that I have [affects] peripheral vision in my right eye, but it's actually in both eyes because where this mass sits, it sits on my vision center. Because it cuts on the right side, I can still see you on this side. So I can see this, but I can't see this.

It's a challenge. When I go to read, the way my oncologist explained it is the words will fold back on each other. A lot of people do it, living with it. A lot of people do. It's my turn. Life deals us challenges, and you've got to go with it.

In my research, the first thing I found reference to was the band Irie - which people in this town still talk about. In the first article I found in The Dispatch [April 19, 1984, a preview for the upcoming Reggaefest '84] you're referred to as the leader. How did that start?

I moved to Columbus in 1982, '83 [and] I started playing with Irie pretty quickly. Somebody put an ad in the Lantern [OSU newspaper] asking for a reggae drummer and a reggae bass player. I went and met this guy and said, "Well, I don't know how to play reggae, but I'll play it." We did the [weekly] open stage at Bernie's Bagels, where he played guitar doing a Bob Marley song, and I was playing bongos.

We did that for about three weeks or four weeks until we found a bass player, and it was a three-piece reggae band. Called in Scott Lake. He was the brain child, and he said, "We're going to call it Irie." We started playing every Sunday and then every Wednesday. A band I played with later, The Swimmers, [had a residency]. They were a Deadhead band from Upper Arlington with a big following, and Irie would play between the sets.

Irie went through a bunch of changes; Scott left and I got the name. We got [singer] Deighton Charlemagne from another band; he grew up in St. Lucia. When we came together, Irie was truly born.

Did that band tour much?

Oh yeah, all through the region. We would play Buffalo, New York, on a regular basis. Louisville, Kentucky. A lot of college towns: Lexington, Frankfort. And [here in Columbus], Cliff Hardy and Hugo Cabrera did a bunch of shows even before [Cabrera's club] Skankland. An outdoor venue called Echo Lake, Valleydale Ballroom. We opened for Steel Pulse four times. Culture, Jimmy Cliff, Gladiators.

The problem was we were so visible; we had a very good reputation; we were an Island band because Deighton could play pans, steel drums. Cliff Hardy brought in Deighton and wanted to be our manager.

But I don't know how we supported ourselves. We had an eight piece band. Our overhead was crazy, too, because we had to carry in our sound system and all of that stuff. We rented it. We rented a truck to move it in. We made maybe $50 a week [per person]. Some of us were married and had kids.

And one day I just couldn't do it anymore. We were in East Lansing, Michigan. I got up in the morning. There were beer bottles all over the place. Everybody still sleep. I had stopped drinking, and I'd stopped smoking weed. And clarity said Carlton, it's time for you to go.

I went and got a Greyhound bus to Detroit [before heading back to Columbus]. I went there, and I shed a tear because I felt it was my baby. I was very possessive of Irie.

Did you do anything musically between Irie ending and joining the Mob?

No. I got back to Columbus on the bus, and I went to [local scene hub] Stache's and Little Brother's because I think it was a Friday. I ended up there because a lot of times you go there and drink, have a good time. And Montie Temple was a bartender at Stache's.

He's listed as a producer on the earlier records and credited with pre-production on the major label stuff, and there's a song about him.

He's the fifth member of the Mob, totally. He was there before me, and he was there when we all ended and he's there now.

I saw a flyer on the mirror in back of the bar that said this band's looking for a drummer, RC Mob. I said, "Montie, what's this about?" He says, “Oh, this band that plays a bunch of covers and stuff is working on a record.” They'd just done their first EP. I asked him, "Well, can you set up an audition? What do I got to do?"

I got an audition the next week or something because the drummer that they recorded [debut] Land of Sugar with was looking to get out. He was holding the chair until they found somebody. I got that audition and it was love at first song, bro.

You knew immediately?

You know what? I did. I'd been playing reggae, I don't know, three to four years. [Now,] we were playing Led Zeppelin, James Brown, Prince, because at that time they were playing three sets.

David Ellison was instrumental; he was very good at working to make that band successful [even early on]. I said, "I just ran a band for the last three years. I can step..." [But I got to] just take a back seat. He was really good at meeting people. He was really good at numbers; he was a businessman.

What was that first show like? Do you have memories of it?

When I joined the band, our first gig was at Apollo's on High Street [the second story of a complex that also included the original Skully's location]. There were probably about, I don't know, 20 people, something like that. Loading in on the pee-infested back stairs. Oh, my God. The first gig was pretty low-key. However, the very next one, it was three times that many people, and we were like, wow!

For the first three years, four years, it was that kind of a climb. The attendance blew us away. We'd go down to Cincinnati and it was the same thing. It was small at first. Then each time we'd go back, it would double or triple. We were marching up this fricking hill, man, and I had no clue about the alternative scene. Every city - some slower than others - we were having that reaction.

REM, who's that? I didn't know them. I knew of the Chili Peppers, but I didn't... songs on their penises? What is wrong with these guys? But my eyes were opened by once I got in the Mob and traveling and got to know all these other underground bands that I had no clue existed. It was just a whole new world for me.

In the early touring days, was there a band that stood out?

Yes. Fishbone. The first time we played Bogart's was opening for Fishbone. There were probably 200 people there, because we were both starting out. But the Mob - especially Happy and I - we were watching these guys. They were at least ten years younger than us and they were fucking amazing.

Can you talk about signing to the Moving Target sublabel of Celluloid? With label mates like Peter Zaremba from the Fleshtones, Sly and Robbie, Yellowman, [Fela Kuti bandleader] Tony Allen...

[Owner] Jean Georgakarakos signed us himself. That deal was in progress when I joined because they had put out Land of Sugar on [Curt Schieber's] No Other Records.

Celluloid was doing distribution, and they were great at getting to the ground troops. They took care of a lot of advertising, promotion, making sure [your records] got out and [then] pushing them in the stores.

Could you talk about the writing and recording of [first record for Moving Target] Omerta? Did the songs grow out of jams, or did certain people bring mostly-finished songs in to be fleshed out?

There was a little bit of everything. Some of it was written before I joined the band; they already had songs. Then when I joined the band, we just started writing. A lot of times, [it went] Carlton, play a drum beat. Then Happy would get in there. B would come up with a guitar part, and David would just hit the record button and start singing.

David, he's just a wit. The shit that would come out of his mouth is like how do you even think of this stuff? A lot of times, it would be so funny. And we did that with a lot of it., [like] "Love and Tuna Fish." But then B brought in "Red Telephone," which is the riff, and I came up with the drum part, Happy came up with his part, and David came up with his part. I mean, we worked as an equal partnership a lot. But yes, B would bring in stuff, but we all claimed it as our own. It would become different later.

In the wake of Omerta, reviewers like Robert Christgau said "unlike other umpteenth generation new-wavers they have identity to burn;" the Chicago Reader said "Mutant funk from Ohio hasn’t been this memorable since early Pere Ubu."

I was just listening to Omerta on the way over and it still sounds remarkably fresh. Did you have a sense while making it that it was a special record?

I don't think [at the time]. When we did it, we had no clue; [but] just after the record came out and we were supporting it, we'd go to after hours parties where they're playing the record. That they just heard [live]! All of that amazed me. Because number one, I [usually] wouldn't go see a band twice.

But [then to] have all these of folks - fans, friends, whatever - who would come every time. And I'm like, wow, that's deep. To give that kind of support and to show that kind of love. And obviously they're getting something out of it. Because they wouldn't be doing it

To me, it was like, this is fucking cool, man.

The last record for Moving Target was SNOB [Something New, Old, Borrowed] which collected Land of Sugar, a live set from the Ohio State Fair, and a couple of additional tracks. As original material got more prominent in the mix, covers stayed important. Everyone talks about the Ohio Players covers but I was struck by that ripping version of James Brown's "The Payback" on Omerta and the covers of Led Zeppelin's "Immigrant Song" and Quincy Jones' "Body Heat" from the live tracks on SNOB. How did those covers get chosen?

I was the newest kid on the block and they had things in the works.[Many of] these songs were in the set. "Love Rollercoaster," "Immigrant Song," "Sweet Emotion," they were playing that before I joined. I loved this band, especially in the beginning, because it [meant] playing all these songs that we hear on the radio that I wanted to play.

I love Aerosmith. But [at the time] I wouldn't even know who they were. I just listened to the music and said, "Wow, that's cool." And I think a part of my falling in love, in the beginning, was because of the choices. We did "A Whole Lot of Love," God, it was great doing that. And David would do this excellent version of Rolling Stones.

I didn't have the library of bands to pull from; David, Harold, Montie, they could sit up there and go through and give you the liner notes. And me, I'm like... I don't know who that is. But [rock is] what I loved when I was 12, 13 years old. Back then, radio stations were segregated in a large way. So I would be listening to, as we called it, white boy radio.

Spin The World

Tell me a little bit about signing to Sire. I know co-founder Richard Gottehrer co-produced the records with hip-hop producer Eric Calvi.

It was Seymour Stein who signed us. And I didn't realize the importance of that or the significance of it. Seymour came to first the CBGBs, when we were doing New Music Seminar. He brought Richard Gotterher there. But then he came to Chicago's Cabaret Metro and we met him there.

Then we went to New York and met him in his office, because several people were courting us at the time, SPK Records, Reprise, which is of course another subsidiary of Warner Brothers, there were several others, but we obviously went with Sire. I wish we'd taken more advantage of that. For Seymour to sign us is a pretty big deal.

It puts you in this lineage with the Ramones, Blondie...

Exactly.

And Spin the World is a case in point. The cover, the tights, and the royalty, were kind of my idea because I was in theater. I was like, "Well, this is kind of cool, right?" But it also shows that I didn't know anything about the fucking business because we shouldn't have done that.

I mean, I kind of get it. It looks different from anything other on the stands and [the wordplay with] Royal Crescent Mob.

Right. And I wish Seymour had said, or their art department or somebody said, "You know what, you might want to reconsider this, and we'll tell you why." But instead, they let us do pretty much what we wanted to do.

Tell me about recording Spin The World. That was at Bearsville in upstate New York, right?

When we got to Bearsville, it's Todd Rundgren's place; it's beautiful. We did a week of pre-production in a building on the property called the Barn. You'd sleep in the Barn, and set up your gear: it was camp. Eight hours a day, however long. You started working on getting sounds, getting songs, well, getting them ready.

For our recording process, we did everything pretty much live. Back then you didn't have the editing tools that you have now. So you really worked to get a great drum track - I was busting my ass for the first week to get it right - because then you can layer everything else. It's great if you can all play together and get a great take; but that wasn't the primary goal.

It took, I don't know, we were there about a month, I think. It was great. And Sire was footing that bill. I can't even remember, did we have a per diem? But we had Zelda on the television and a big bag of weed. I was good back then.

Were you writing up there or did you have the songs ready?

No, by the time we got there we had the songs. I think on the next record, Midnight Rose's, there might have been some writing in the studio. Coming up with songs for Spin the World, because we got into a routine where we were getting together pretty much everyday. We would get together for two or three hours a day working on song ideas.

Could you talk a little about touring at this point, what opportunities did the major provide you and how did that change?

We hooked up with a booking agency I think was called Triangle. We started [longer tours] with bands like the Dead Milkmen, the Replacements.

I assume there's a story about touring with the Replacements.

Oh, man. They wanted to steal me. Paul Westerberg said, "Carlton, come on man, come on. I'm ready to fire Chris." And I was like, "Dude, what the fuck are you talking about?" But the funny thing is, I don't know what was going on with them, but Chris would be in the dressing room by himself, not drinking or anything, then the other three would be out.

We did three-and-a-half weeks across the country at some point together, and they were cool. They loved to party. And that's their reputation because I didn't know them [before]. The first gig we played with him was at the Graffiti in Pittsburgh. And oh my God, at soundcheck, they were just gone. And I was like, wow. I [filmed] some eight-millimeter stuff [from the gigs].

Legendarily, you all toured with the B-52s. I found that mentioned in a couple of Dispatch articles.

Well, that was Cosmic Thing; they'd been off the scene for five years [live]. "Channel Z," "Love Shack." They were on Sire, we were on Sire...

And you were both dance bands.

Right. It was three and a half weeks in '89. We started at the Fillmore West, and there were two sold-out shows. It might have been three. And I remember going there and checking them out during their first sound check. I was like, "Oh, they sound great, but we got this, we got this."

I mean, we could have been, James Brown. It didn't fucking matter, man. Because [their fans] didn't want to hear nobody. And I mean, when you go in there, it was general admission so people were already at the front of the stage when we went on. It was a packed house. And from note one, it was Boo! And it's like, wow, this is going to be hard. This is going to be a hard tour.

I mean, we had fans there, but of course you're playing 20,000, 10,000, 15,000 seaters, and it doesn't matter. [Most of them] don't care. And there were some places that were nice, but it was definitely an eye-opener. And you get up there and you just do your do and get the fuck off the stage.

But it was great. They were so cool. Freddy [Schneider], all of them, they were just very hospitable. And they were great players, man. I mean, Sara Lee, she was the bass player.

Oh man, one of the best. I saw her in that version of Gang of Four in the '90s and with Ani Difranco a few years later.

At one point when we were recording, her band, the Raging Hormones, played in Woodstock, New York. Because that's where we were hanging out. I don't even know why they were playing there. But you had Sara Lee, you had Charley Drayton, you had Steve Jordan. That's the only time I met Steve Jordan.

For all that touring, we never went to a bus, we were still in the van. I only did one bus tour, with the Twilight Singers later.

How did that evolve as you moved into Midnight Rose's? Did you feel pressure or have an inkling that would be the last record for Sire?

Not until later. [Other members] may have been. And maybe there was talk about this being the last record, they knew they had to get it to us regardless. I know it seems so weird, but I was, just oblivious to the accounting. I was thinking that, "Well, they're going to stick with us until we pop."

The challenge that we came [up against] was just writing the songs between the four of us and coming up with ways [to change it up]. We would go in pairs and say, "Okay, David and Carlton, you guys go write a song. Okay. B and Happy, you're going to write a song."

I think we should've stuck with our formula. Once we got away from that, I think that is what actually put a nail in our coffins.

Midnight Rose’s

Midnight Rose's sounds more like a radio rock record of the time.

It was intentional. I think we wanted to be more clever. We wanted to be diverse and Happy kind of started pulling away. I don't think it was challenging musically. Not that it wasn't challenging enough for him, but he wanted to do his own stuff.

And you're pushing because you think you're going to get it, right? And they're saying, "You going to be the next thing. This is it." But things weren't exactly lining up with what they were saying.

I remember a KROCK show in Arizona where [Belgian techno band] Front 242 was headlining. We played at three or four o'clock. I [still] had a great night that night. We had a bunch of bands open up for us and pass us up: Primus opened two or three times [and it was a] total match. 311. We got to play with Ugly Kid Joe right before their big hit.

[Management] saw the storm clouds coming, but I didn't. It was when we were at the KROCK show that things started coming out of the woodwork then, because our manager wasn't there, which was weird. And so that's when Happy, there were hints being made that we were being dropped. And I was like, "Really?"

Did you come out of that determined to make the last record, Good Lucky Killer that ended up on Enemy? It feels like it goes further in some of those other directions. Did you expect that would be your final statement as a band?

No. We wanted to make another record.

We'd gotten dropped from Sire, and we were just knocking on doors and not realizing that, well, they're not going to pick up because you're knocking. That's for sure. Especially if you were dropped on the level that we were. We went to Capricorn Records; we went to, I don't know, several [labels]... Capricorn was mine. I was trying. I got some response.

Aren't they more of a Southern rock label?

Yes. But when we were looking at it, they were courting 311.

And one of us found Michael Knuth. I can't remember how. Maybe he showed up at a gig?

While researching this, I didn't realize you had a record on Enemy and I have a lot in my collection on that label but they're mostly hardcore jazz records: Last Exit, Sonny Sharrock, Friction, Defunkt. And another Bill Laswell connection - was there ever a conversation about him producing you?

Not that I know of. I know he's a great bass player and producer.

You don't have to go into total detail, but how did it end?

Happy quit the band. And that was not pretty for me, because he was my best friend. We were having a band meeting downtown and Happy and I rode down together. At the end of the band meeting we were talking about going on tour in Europe and stuff like that, and Happy basically says, "Well, I'm actually quitting the band." And I was blown away.

I knew he was working with Howlin' Maggie, because I had done a couple of shows with him as Howlin' Maggie while being in the Mob. So needless to say, when he dropped that bomb, I said, "You got to find another way home, huh?"

When the Mob broke up, was there a recuperation period? I know you were involved in Twilight Singers for a while.

After the Mob broke up, I was trying a little bit of everything. I was playing with The Swimmers, or it might have been the Electric Hurling Stones at that time. They had two drummers.

So full Grateful Dead. I mean, I know other bands had two drummers, the JBs for instance.

Absolutely. A lot of times, I would just play a whole rack of Rototoms and congas, and I'd have a snare up there. So I did several different configurations in terms of the double drum setup. But I did that with two different drummers. And playing with two drummers can be... If the other drummer is listening, it's fine. I'm listening, are you?

[In those years I was] just trying stuff. Writing. I played in several different reggae bands: The Decals, the Skankland rhythm section were a house band playing every Tuesday.

Tell me a little more about Montie Temple. You mentioned you owned a studio for a while?

Yeah, Land of Sugar. That was definitely after the Mob; we wanted to record. It was all about recording, so we got a warehouse over there on Grandview. Because we were there, I don't know, from '90, I don't know, four years? Something like that. We rented out the rehearsal space. And then, for those who wanted to record, Montie could offer those services.

But it was pretty basic and simple. It wasn't like Tom Boyer's spot or John Schwab, those crazy studio guys that had really good spots. We did that for several years.

Tell me about the connection with [New York metal band] 24-7 Spyz?

I turned the label on to 24-7 Spyz. I want to say, at that particular gig where they introduced themselves, we were opening for Living Colour.

Vernon Reid would come and see us regularly. Maybe he did that with everybody, but I know he did it with us. When [Living Colour] did their first gig as Corey, Will Calhoun, Muzz, and Vernon, we opened for them, and it was at Maxwell's in Hoboken. And so there was that whole Black Rock Coalition.

[24-7 Spyz] gave me a demo tape for "Harder Than You." They said, "Hey, can you check this out? Can you check this out?" They introduced themselves, and Jimi [Hazel] and Rick [Skatore] were like, "We should have been on this bill."

I want to say six months later, something like that, we [the Mob] were at Sire Records in New York talking with our A&R guy, and he said, "Hey, I want to show you something. There's this new video that's coming out." And I said, "Okay, cool." And it turns out, it's “Jungle Boogie” by 24-7 Spyz on Headbangers Ball. And they were getting it ready for that, and I'm like, "Wow." The next thing you know, they're flying.

Those first three or four records are so good.

I know, man. And we're still friends. I talked to Rick about a month ago. Jimi and I are still friends.

You're on several tracks of Heavy Metal Soul By the Pound, so you went deeper into that world after leaving the Mob.

From the time they gave me the demo tape, we stayed in contact. When he was trying to put together a band called Black Angus. And so we were writing songs for that. He was writing songs for that. So I would go to New York and California, and record with them I was in and out. But man, they're some great musicians.

They came and did some recording here, at Land of Sugar, the studio Montie and I had in the 90’s.

And when I listen back, I go, "Aah," because Joel Maitoza was a beast. He is a beast. I love Joel's playing. And that's why I get why Jimi, when he'd listen to me, sometimes he'd go, "Mmm."

How did you reunite with Happy for the version of Howlin' Maggie that you were a part of?

In '98, I think it was. Lance Ellison, he's a prominent guitar player. Right now, he's doing a yacht rock band, but he's a great player. But we're the same age, we toured a lot together. He was with me in The Twilight Singers, and we did a band called The Crawfords.

So that second record... I know Happy and Lance were working together, and I think Happy gave me a call and said, "Hey, you want to do this?" And I said, "Cool." I said, "Who's playing bass?" And they didn't have anyone, so I said, "Let's get Christian Hurd."

Ah, you brought Christian Hurd from Templeton into that lineup.

Yes, yes, yes. Because Christian and I were in a band, Tater, with Jabali Stewart.

[After the first lineup of Howlin' Maggie split up,] Happy's just gotten Pro Tools. So he was working on his recording chops and we all know that learning curve is a mother, man. We did Hyde, and I think that came out in 2001. I talked to Happy recently, I said, man, we should get a couple of these remixed man,

Then we toured for four years, something like that. Then I couldn't keep doing it because it just wasn't enough money. And at that point, I was working at a call center. I was doing that full time pretty much.

Could you talk about your sons' band a little, Chickenhawk Birdgetters? How's it feel seeing them on stage?

That came into being about ten years ago. They do that jazz or avant-garde jazz-rock. I played with them this past ComFest. It's interesting, because they get together, at this point, in the last five years, they've only been doing ComFest, and they get together maybe two weeks before, learn something, and then they just go play. <laughing> I'm like, "You fucks." They play off of each other. And they're good at that.

Jahrie has played in a bunch of different bands. And then his brother Juhriah, he plays bass and guitar. And he's helping me with some music now. I love the idea of playing with my son. I really want to play with my other son, but he's a drummer. So we can do the double drum. But I thought, "Maybe I'll just play keys." I could do that.

Did you have a lot of contact with various other members of the Mob, since breaking up?

Out of all of them, I do.

People have been asking over the years, "When are you guys going to do a Mob reunion?" And I never thought it would come around because David doesn't sing anymore. He hasn't been practicing his art for 30 years. Obviously, Happy, B, and I play.

Once I got my diagnosis, I was like, "I'd love to fucking play one more show." I approached the guys and said, "Hey, let's do a Mob reunion, because I don't know how long I'm going to be here. And I think it would be great for us, because it was the time in our life when we were all having a great time." They're saying from 12 months to 24. And of course it can go beyond that, but we are not allowed to say that. There's no guarantee. They said, "Fine." We've got a great cause [for the proceeds,] cancer.

How's the reunion preparation going?

It's been great. [Happy] hasn't played our songs until this past week, since he left in '94. When we're talking about that, he's like, "Man, I haven't touched these." He said there was one other show where we did two songs and he touched those, but overall, he hadn't played it.

It's been cool because he and I have been practicing just the two of us. And he was like, "Wow," he's just relearning this stuff. And it's me, I have to relearn it too, but it's not like these songs are that difficult because they're not. But they're fun to play.

B. still plays in church; he doesn't play in bars anymore because he gave all that up.

We're getting together on Zoom calls, throwing out suggestions for a set list [before getting together for full band rehearsals in Columbus].

That's fantastic. I'm looking forward to seeing it. Anything else I didn't cover?

You know what? Ain't no room for hate, my man. We got to love. But for me, specifically, I just want to give thanks for the time. That I've had. That I have now. I feel blessed. I feel grateful. I've got five kids. Seven grandkids.

Dude, I've done my part as far as nature is concerned. So I don't know. I'm in good place, man. I'm in a good place, emotionally. Physically, I'm in a good place now. I know that's going to change. I appreciate [all of it].

The RC Mob

Richard Sanford writes about various corners of the art scene, mostly in Columbus, for a variety of outlets. He grew up here and loves Columbus, even when it pisses him off.